I was recently meeting with a leadership committee tasked with overseeing a layoff. It was a grim room filled with apprehension and resentment. No one was happy to make these difficult choices, but it was understood that a reduction in force was the last available option to save the company.

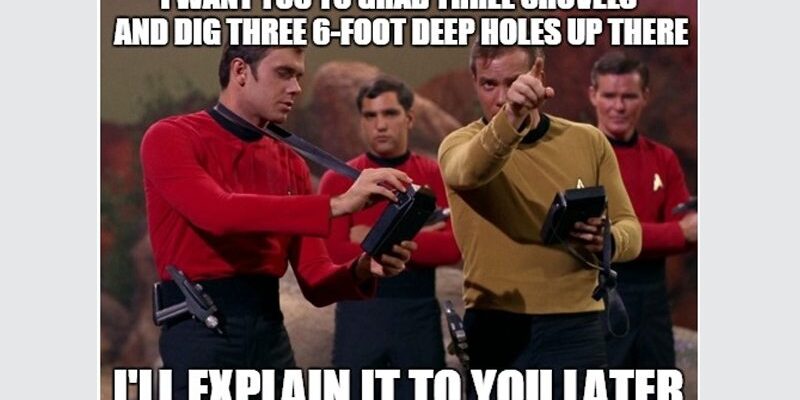

The committee’s conversations were analytically based, as if de-personalizing the decisions would make them easier. Human resources did a nice job preparing quantitative research complete with charts and graphs. Performance (division, department, and employee) was summarized on spreadsheets without identifiers to allow for unbiased analyses. And everyone was armed with a calculator to crunch the numbers. It was at this moment when I began empathizing with Captain Kirk—we were both responsible for choosing the “redshirts” undertaking their last expedition.

If you are not familiar with the term redshirt, it is commonly used by Star Trek fans when referring to the characters dressed in a red uniform. It seems that anyone wearing red has a higher fatality rate than other characters on the show. This is not just conjecture. When SiteLogic crunched the numbers, they found that 13.7% of the crew died during Star Trek’s three-year televised mission; and of those who died, 73% were redshirts.

By comparing real-life layoffs to the fictional deaths of USS Enterprise staff, I am not trying to minimize how awful is it to be laid off, nor am I undercutting the immense pressure leaders are under when implementing an initiative that will negatively impact so many people. What I recognized sitting with that committee through hours of discussions is how easy is can be to begin thinking of employees as anonymous redshirts.

Redshirting the workforce may sound callous, but let’s consider it from the leader’s viewpoint. How many people can a leader really be expected to know? In a smaller company, you should be acquainted with everyone, however as the populace grows into the hundreds and then thousands, no one can realistically maintain a relationship with each person. Throw in satellite offices and a swelling organizational hierarchy and the once start-up now feels beyond one leader’s control.

My advice is to avoid the apathy associated with accepting others as redshirts. They are not expendable, even if Star Trek treats them as such. Your redshirts are responsible for getting the work done. Unlike the layers of management, redshirts touch your product and maintain relations with your customers. Their value (and your ability to make sure they feel valued) is a primary competitive advantage for the lasting success of your organization.

Being unfamiliar with every employee doesn’t excuse you from continuing to make an attempt. This direct contact not only gives you candid insights in the culture, but also provides you the opportunity to tap undiscovered potential and unearth the many ways your organization can be improved from the people with firsthand access to the processes.

You may read this and decide to uphold your redshirt practices. Be warned. If you choose to use them as a disposable first line of offense, it is only a matter of time until they grasp the stigma associated with the redshirt. Engagement will plummet, productivity will suffer, and turnover will spike faster than a Tribble reproduces.