I recently read a fascinating article by Rebecca Solnit on how being born to privilege has had a corrosive effect on Donald Trump and his presidency. She discusses the ways an individual raised in a protected bubble of wealth and power becomes isolated from the rest of the world. After reading Solnit’s piece, it’s evident that the trappings she associates with Trump can become obstacles for all leaders. Here are three lessons that sound out:

Setbacks

We gain awareness of ourselves and others from setbacks and difficulties; we get used to a world that is not always about us.—Rebecca Solnit

There is a mentality amongst some leaders that acknowledging failure is a weakness. As a result, they shift responsibility (i.e. blame others) so they are no longer accountable, artificially reframe setbacks as new opportunities, and/or outright change the end-goal so the outcome can now be viewed as a win.

While “not failing” may feel good, it is a false sense of satisfaction. Leaders must build the thick skin necessary to accept and learn from disappointment without carrying the weight of feeling like a failure. Otherwise we risk becoming overly sensitive and brittle, unequipped to make the adjustments necessary to rebound and adapt.

As leaders, we must also allow others to fail. Solnit writes of rich college kids who are not allowed to fail because their parents “[keep] throwing out safety nets and buffers” that protect them from experiencing adversity. As nice as this may sound, when we live without consequences, our lives become inconsequential—we cannot feel the highs of achievement without also having faced the lows of failure.

Self-Reflection

Power corrupts, and absolute power often corrupts the awareness of those who possess it.—Rebecca Solnit

In Hannah Arendt’s book On the Origins of Totalitarianism, she promotes the need for an inner dialogue where we can cross-examine ourselves, where we can ask the difficult questions. If we can master this skill, we are better equipped to have these discussions with the people around us. If we lack the ability to self-interrogate, we are prone to suffer from, what Arendt calls, the banality of evil, i.e. “the inability to hear another voice, the inability to have a dialogue either with oneself, or the imagination to have a dialogue with the world, the moral world.”

Obliviousness

Equality keeps us honest. Our peers tell us who we are and how we are doing, providing that service in personal life that a free press does in a functioning society.—Rebecca Solnit

We need people in our lives who have the ability to provide unfiltered commentary. These individuals cannot be fearful of repercussions, nor can they hold back in the hopes of gaining some type of advantage. They must be willing to give it to us straight and we must be open to what they are saying. Otherwise, we risk becoming oblivious.

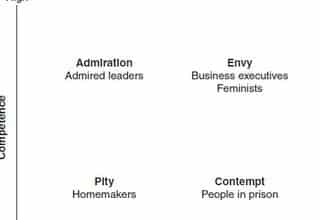

Obliviousness is not a sign of low intelligence, but an indication that the leader is sequestered from information that runs counter to their viewpoint. It tends to happen over time as we weed out those who are the bearers of bad news, those who are perceived as not being “on board,” and those who are damaging our precious self-esteem with their critique. Before we know it, we are surrounded by yes-men and sycophants who tell us what we want to hear versus what we need to hear. In the end, not only are we alone, but their biased feedback has infected us with delusional thinking, faulty decision making, and a general lack of insight into how our team and the population-at-large are feeling.

Being in a position of power can be lonely, but it doesn’t have to. Leaders must seek and foster relationships outside of their power structure. Our associates keep us honest. They ensure we remain grounded and in touch with reality. And they provide the feedback, criticism, and advice that, while not preferable, is essential to avoiding the impairments of corrosive privilege.