Have you been watching the Netflix series, The Crown? This biographically-based, historically-accurate program depicts Queen Elizabeth II and England’s government in the 20th century. The visuals are incredible as is the insider perspective of the relationships within the monarchy. But from a leadership stance, what I find most fascinating are the interactions between the royal upper-class and the “commoners.”

The first time I was taken aback by the reverence to the Queen is in the first season. Immediately after her coronation, the Queen’s sister and mother bow as Elizabeth enters the room. They didn’t bow an hour before the ceremony; it took a crown to trigger such veneration.

I have a hard time grasping the idea that one social class of people are inherently superior to another, let alone being bow-worthy. However, while I may not be focused on it, research shows that social class is engrained into our psyche and consistently effects our behavior and decision making.

According to a study published in the British Journal of Social Psychology, our social class remains as influential on our identity as gender and ethnicity. From a behavioral aspect, the research found that working-class people are more likely to exhibit eye-contact and head nods versus the more distant non-verbal patterns displayed by middle/upper class participants.

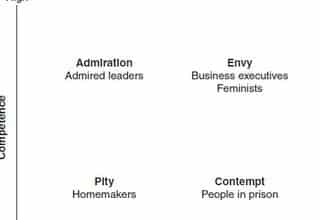

There are also psychological consequences resulting from the social class with which you identity. Because they lack the resources to mitigate disasters, the working class are more likely to see the world in terms of forces that must be acclimated to or coped with, resulting in higher degrees of watchfulness and caution. This can be beneficial, but it can also lead to feelings of powerlessness and a fatalistic mentality. On an upside, the working class possess a greater ability to see how external events shape the emotions of others, have more substantial interdependent relationships, and experience elevated levels of social engagement.

On the other end of the spectrum, the middle/upper-class have a greater sense of perceived control—they see the world as something to shape and influence, not as an opposing force. This group is also more motivated by personal goals, which can lead to greater selfishness, less empathy, and a higher tendency to lie in negotiations.

Unlike the British monarchy where birthright determines social class, there’s a belief that America is free from pre-determined caste systems—with enough hard work, social mobility is available to everyone. While technically true, the research found that those from lower social classes are more likely to feel out of place in middle/upper-class situations. Even as they move up the ladder, those from a working-class background are more likely to perceive the opportunities available to them as second class.

While our class is deep-rooted in our subconscious, it can serve to motivate us without causing self-doubt. The study shows that by merely giving people an accurate depiction of their socioeconomic standing, they are more receptive to change and more inclusive of other social classes.

The lesson for leaders is simple: know thyself. Come to grips with your upbringing so it doesn’t become an excuse for your insecurities. And help others break free from the mindset that’s limiting their perspective and potential. It may not immediately lead to a throne, but it’s a necessary step on the path towards coronation.